By Dana P Skopal, PhD

In our last blog we looked at planning your message. The next important step is to structure your message in a coherent – or clear – format.

Coherence covers both the ordering of key points as well as links between sentences. We cover this term in our writing workshops and often refer to it in our blogs. Perhaps think about coherence as logical connections between report sections, paragraphs and sentences and what signposts you are giving to your reader. The linguistic terms that can describe the steps are Theme and Rheme (see the work of Michael Halliday), or Given and New (see the work of F Daneš and P Fries).

In English, what comes first in the sentence (or clause) is the focus of the text.

- Theme: what element (word, group of words, nominal group) that comes first in the sentence or clause (ie given or known information)

- Rheme: what is left over (that sets out the new information).

Nominal groups, which describe the who or the what, contribute to the organisation of a text through their placement in the Theme and Rheme.

Our research has shown that if you place unknown or new information at the beginning of your sentence, which is the Theme or Given part of your sentence, or your subject is far too long (over 12 words), then you will most likely lose your reader. The links to your information also come from the terms you select for any headings in your document.

When writing, make sure the subject of your sentence (the first part, the Theme) is not too long. Then follow the Given + New information structure, expanding on your information after the verb. Here is an example from our article in the journal Text & Talk [see below].

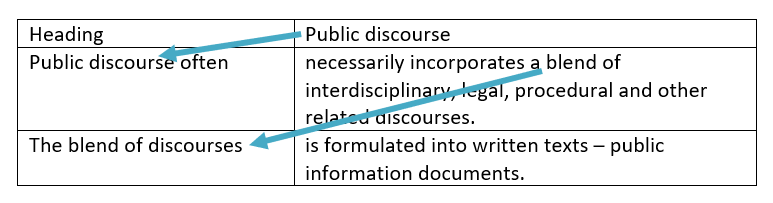

The heading is public discourse, which then becomes given or known information. The next sentence states:

Public discourse often necessarily incorporates a blend of interdisciplinary, legal, procedural and other related discourses.

In that sentence, the new information is after the verb ‘incorporates’ and describes the different discourses. That blend of discourses then becomes known information, which you can use at the beginning of the next sentence.

The blend of discourses is formulated into written texts – public information documents.

So the new information in that sentence is developed after the verb ‘is’. Aim for this linking of ideas when writing a paragraph, as readers are lost if you place the new information at the beginning of your sentence. These links, giving coherence and structure to the information, are represented below in a table – the left hand column is the Theme and the right hand column is the Rheme (new information).

When you have time read Skopal, D. P. & Herke, M. (2017). Public discourse syndrome: reformulating for clarity. Text & Talk, 37, doi: 10.1515/text-2016-0041.

Copyright © Opal Affinity Pty Ltd 2024